Nuclear Weapons

“Should my country join the TPNW?”

(TPNW = Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons)

Peace Child International held its first Model Citizens’ Assembly on this question on Sunday 10th January 2021. Dr Rebecca Johnson – one of the chief architects of the TPNW, argued the case for a YES answer. James McCormick of the UK Government’s Counter Proliferation and Arms Control Centre made the case for a NO answer. You can see the videos of their arguments here. You can read a detailed report of the event here. You can read a Survey of the audience’s opinions of the event here. You can read the Background Papers on the TPNW issues here.

Ever since the first nuclear weapon was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, Japan on August 6th 1945, the world has been talking about getting rid of them. All of them. For ever. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed between 150,000 and 200,000 people. The Hiroshima bomb had a yield of 15 kilotons. A modern hydrogen bomb has a yield of 10,000 kilotons – and there are still 13,850 of them in the world, many on hair-trigger launch readiness. If there was an all-out nuclear war, millions would be killed in the first few nuclear exchanges. Whole cities would be wiped out. But the real danger to humanity starts as the dust clouds begin to spread around the world – carrying with them the threat of a “Nuclear Winter.” Carl Sagan first drew attention to this consequence of nuclear warfare back in the 1980s. Jonathan Schell described it in detail in his book, The Fate of the Earth. It was immortalised in the TV Film “The Day After” – watched by over 100 million people in North American when it aired in 1983. The dust clouds cause freezing summers which leads to ‘nuclear famines’ as food supplies dry up. The famines kill far more people than the original explosions – as the Winter could last for up to 25 years.

All agree: the presence of nuclear weapons is a threat to the very existence of life on earth. We must eliminate them. The question is: “HOW?” And that is the question that successive governments have failed to answer. Which is why we encourage you to host a Citizens’ Assembly on the subject as, if governments cannot solve the problem of how to eliminate nuclear weapons, we the peoples must. None of us can afford to sit idly by when a computer error, or a terrorist, or a delusional government leader – can unleash nuclear weapons that would lead, inevitably, to an almost total elimination of life on earth.

Let’s have a look at a brief history of how human beings both developed huge arsenals of nuclear weapons – and subsequently tried to reduce them.

A Short History of the Nuclear Issue

The Background to the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons(TPNW) begins on 10th January 1946 when British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, opened the 1st meeting of the UN General Assembly in London, saying: “Atomic Energy is an invention fraught with possibilities, on the one hand of danger, and on the other of advantage to the human race. It is for the peoples of the world, through their representatives here, to make their choice between Life and Death.” On 24th January 1946, those representatives made their choice in the first ever UN General Assembly resolution. It agreed to set up a Commission to deal with the Problems raised by the invention of Atomic Energy – starting a long history of talking and discussing, rather than taking action on, the issue which, arguably, continues to this day.

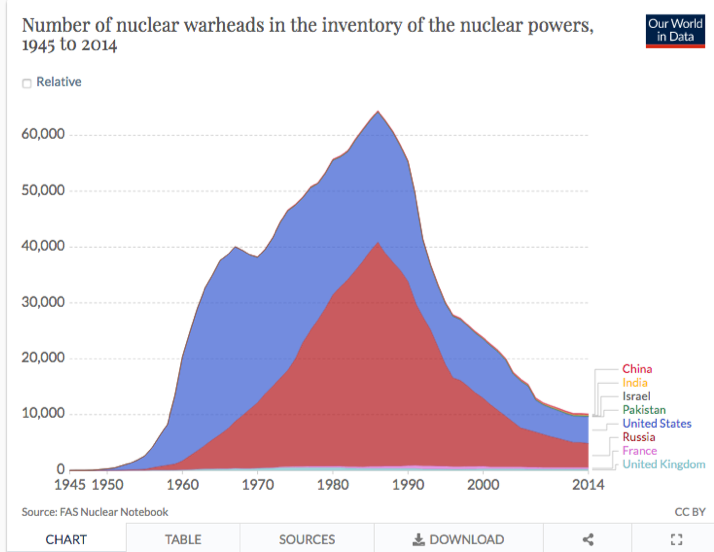

Events were not kind to the Commission: first, the Soviet Union exploded their first Atomic Bomb. 3 years later, the US exploded a hydrogen bomb – a “Superbomb.” 3 years after that, in 1955, the Soviet Union exploded their’s – and the arms race / Cold War was on with ever-increasing arsenals of nuclear weapons on both sides. The UK exploded its first atomic bomb in 1952; the French in 1960; the Chinese in 1964 – and Israel in 1967, according to the revelations of Mordechai Vanunu – a whistle-blower. By 1986, the number of nuclear weapons in the world had reached a peak of 70,300, the vast majority of which were in the Soviet Union and the USA:

In parallel, citizen action against nuclear weapons intensified. CND was founded in November 1957 and the first Aldermaston march to the UK’s Atomic Weapons Establishment happened at Easter 1958. It became an annual event, with over 100,000 people gathering in Trafalgar Square, Easter 1963.

From 1981 to 2000, the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp protested the presence of Nuclear weapons on British soil and, on June 12th 1982, a million people gathered in Central Park New York to demonstrate against the existence of Nuclear Weapons and the Cold War Arms Race. A nuclear freeze movement spread across the United States and Citizen’s Diplomacy movements sprung up between the USA and USSR, helping to end the Cold War by 1989. From then on, the number of nuclear weapons in the world began to drop, even though India, Pakistan and North Korea acquired nuclear weapons.

On 1st July 1968, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was signed in London, Moscow and Washington by all the nuclear weapons states. In Article VI, it states: “Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” It was largely because, after 50 years, the parties to the Treaty had failed to deliver on that promise, that the UN General Assembly began the process that led to the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The governments of the 5 official Nuclear Weapons States still feel that the NPT is sufficient to deliver on nuclear disarmament, pointing to the fact that they have reduced the number of nuclear weapons from the high of 70,300 in 1986, to less than 14,000 today. They, along with all NATO members and Nuclear Weapons States, boycotted the TPNW negotiations and did not sign it. On March 5, 2020, the Foreign Ministers of China, France, Russia, the UK and USA issued a statement saying: “We remain committed under the NPT to the pursuit of good faith negotiations on effective measures related to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control. We support the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all. The NPT continues to help create conditions that would be essential for further progress on nuclear disarmament.”

122 UN Member States felt differently, voting on 7th July 2017 to pass into law the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which states in Article 1: “Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to… develop, test, produce, manufacture, otherwise acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.” And, in Article 4: “Each State Party shall cooperate with the competent international authority for the purpose of verifying the irreversible elimination of its nuclear-weapon programme.” On 24th October, the 50th UN Member State (Honduras) deposited articles of Ratification at the UN meaning that the Treaty will enter into force on January 22nd 2021.

British attitudes to nuclear weapons have shifted: from the full-throated opposition of the Aldermaston Marchers, CND and the official Labour party commitment of the 1980s to “Unilateral nuclear disarmament,” the pendulum has swung back to greater acceptance of the Trident programme: Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent. (Many question its independence saying that the UK Government would require US, or NATO, approval to launch its weapons.) In 2006, the Labour Government committed to renew the UK’s Trident nuclear deterrent, a position endorsed by the Cameron-Clegg Coalition government in 2010. In 2016, parliament voted by a majority of 355 to deliver a multi-billion pound Trident renewal programme to enter service in 2028. In a famous exchange, Prime Minister Theresa May affirmed that she would “push the button” to launch a nuclear strike; Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition, said that he would not and gave Labour MPs a free vote on the issue. He and 47 others voted against renewal. 140 Labour MPs voted to renew, 41 abstained. 59% of the British Public support the Prime Minister – rather more than support Britain having nuclear weapons(52%). There has been no parliamentary debate on TPNW.

The UK’s Independent Nuclear Deterrent: A Vanguard-Class Submarine armed with Trident II D-5 Missiles

BACKGROUND PAPERS

For more Background Reading on TPNW, CLICK HERE

Text of the NPT Treaty – Signed in London, Moscow and Washington, 1st July 1968.

See Full Text of the treaty at: https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text

Article VI states: “Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

It was because, after 50 years, the parties to the Treaty had failed to undertake those negotiations in good faith, that the UN General Assembly voted to agree the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW):

Statement of March 5, 2020 by the Foreign Ministers of China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States: “On March 5, 1970, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) entered into force. Today, 50 years later, we celebrate the immeasurable contributions this landmark treaty has made to the security and prosperity of the nations and peoples of the world. We reaffirm our commitment to the NPT in all its aspects. We remain committed under the NPT to the pursuit of good faith negotiations on effective measures related to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control. We support the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all. By helping to ease international tensions and create conditions of stability, security and trust among nations, the NPT has made a vital contribution to nuclear disarmament. The NPT continues to help create conditions that would be essential for further progress on nuclear disarmament.”

Text of the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

The Treaty was adopted at the UN in New York, 7 July 2017 by 122 countries including Austria, Bangladesh, Botswana, Mexico, Nigeria, New Zealand and South Africa. 1 voted against (Netherlands), and there was 1 abstention (Singapore). On 24 October 2020, the Fiftieth UN Member State (Honduras) ratified the Treaty bringing it into force on January 22 2021.

See Full Text of the treaty at: http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8

Article I states: “Each State Party undertakes never under any circumstances to… develop, test, produce, manufacture, otherwise acquire, possess or stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices.”

Article 4 states: “Each State Party shall cooperate with the competent international authority for the purpose of verifying the irreversible elimination of its nuclear-weapon programme.”

NATO Position:

Stoltenburg Statement – 10 November 2020

https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/opinions_179405.htm?selectedLocale=en

Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg at the 16th Annual NATO Conference on Weapons of Mass Destruction, Arms Control, Disarmament and Non-Proliferation:

“NATO has been at the forefront of nuclear disarmament for decades.

Because our ultimate goal is a world free of nuclear weapons.

Together, we have reduced the number of nuclear weapons in Europe by more than 90 percent over the past 30 years.

But in an uncertain world, these weapons continue to play a vital role in preserving peace.

I know that there are those that look at the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons – or the Ban Treaty – as an alternative solution.

To eliminate all nuclear weapons.

At first glance it seems attractive.

But the reality is that it will not work.

The Ban Treaty has no mechanism to ensure the balanced reduction of weapons.

And no mechanism for verification.

Moreover, it has not been signed by any state that possesses nuclear weapons.

Simply giving up our deterrent without any guarantees that others will do the same is a dangerous option.

Because a world where Russia, China, North Korea and others have nuclear weapons, but NATO does not, is not a safer world.

On the contrary, it would leave us vulnerable to pressure and attack.

And it would undermine the security of our Alliance.”

Brussels Declaration – 2018

https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm?selectedLocale=en

The Declaration states, in Clause 44: Fifty years since the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) opened for signature, it remains the cornerstone of the global non-proliferation regime and has an essential role in the maintenance of international peace, security and stability. Allies are strongly committed to full implementation of the NPT in all its aspects, including nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation, and the peaceful use of nuclear energy. NATO’s nuclear arrangements have always been fully consistent with the NPT. Consistent with the Statement by the North Atlantic Council of 20 September 2017, which we reaffirm, NATO does not support the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons that is at odds with the existing non-proliferation and disarmament architecture, risks undermining the NPT, is inconsistent with the Alliance’s nuclear deterrence policy and will not enhance any country’s security. This treaty will not change the legal obligations on our countries with respect to nuclear weapons. The Alliance reaffirms its resolve to seek a safer world for all and to take further practical steps and effective measures to create the conditions for further nuclear disarmament negotiations and the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons in full accordance with all provisions of the NPT, including Article VI, in an ever more effective and verifiable way that promotes international stability, and is based on the principle of undiminished security for all.

Warsaw – July 2016

https://www.nato.int/cps/us/natohq/news_146954.htm

At Warsaw in July 2016, the Alliance set out clear positions on the issues of nuclear deterrence and nuclear disarmament:

“Allies emphasise their strong commitment to full implementation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The Alliance reaffirms its resolve to seek a safer world for all and to create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons in full accordance with all provisions of the NPT, including Article VI, in a step-by-step and verifiable way that promotes international stability, and is based on the principle of undiminished security for all. Allies reiterate their commitment to progress towards the goals and objectives of the NPT in its mutually reinforcing three pillars: nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation, and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.”

Regarding the prevailing international security environment, they further noted that:

“After the end of the Cold War, NATO dramatically reduced the number of nuclear weapons stationed in Europe and its reliance on nuclear weapons in NATO strategy. We remain committed to contribute to creating the conditions for further reductions in the future on the basis of reciprocity, recognising that progress on arms control and disarmament must take into account the prevailing international security environment. We regret that the conditions for achieving disarmament are not favourable today.”

Seeking to ban nuclear weapons through a treaty that will not engage any state actually possessing nuclear weapons will not be effective, will not reduce nuclear arsenals, and will neither enhance any country’s security, nor international peace and stability. Indeed it risks doing the opposite by creating divisions and divergences at a time when a unified approach to proliferation and security threats is required more than ever.

The ban treaty is at odds with the existing non-proliferation and disarmament architecture. This risks undermining the NPT, which has been at the heart of global non-proliferation and disarmament efforts for almost 50 years, and the IAEA Safeguards regime which supports it. The crisis caused by North Korea underlines the importance of preserving and enhancing the existing framework of the NPT.

The ban treaty, in our view, disregards the realities of the increasingly challenging international security environment. At a time when the world needs to remain united in the face of growing threats, in particular the grave threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear programme, the treaty fails to take into account these urgent security challenges.

The fundamental purpose of NATO’s nuclear capability is to preserve peace, prevent coercion, and deter aggression. Allies’ goal is to bolster deterrence as a core element of our collective defence and to contribute to the indivisible security of the Alliance. As long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.

We call on our partners and all countries who are considering supporting this treaty to seriously reflect on its implications for international peace and security, including on the NPT.

As Allies committed to advancing security through deterrence, defence, disarmament, non-proliferation and arms control, we, the Allied nations, cannot support this treaty. Therefore, there will be no change in the legal obligations on our countries with respect to nuclear weapons. Thus we would not accept any argument that this treaty reflects or in any way contributes to the development of customary international law.

International Institute for Strategic Studies

A nuclear-ban treaty: a question of ideals and pragmatism?

https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2020/11/nuclear-ban-treaty-tpnw

blog by Timothy Wright, Douglas Barrie and Nick Childs

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has reached a milestone at a time when the fate of New START still hangs in the balance. But does the TPNW help or hinder the wider cause of nuclear arms control and disarmament?

On 24 October, Honduras became the crucial fiftieth country to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The development has triggered a 90-day diplomatic countdown to 22 January 2021, after which the treaty will enter into force in international law. It has also rekindled a debate over whether the TPNW helps or hinders the cause of nuclear arms control and disarmament at a time when the future of another nuclear arms-control agreement hangs in the balance.

A tale of two nuclear treaties

The TPNW process has been driven by a moral abhorrence of nuclear weapons, the unarguably catastrophic effects for humanity of a thermo-nuclear exchange and what supporters see as the laggardly behaviour of nuclear-weapons states in moving forward on their disarmament commitments. However, it may also be the case that it is easier for non-nuclear states to give up something they never had. Only one of the first 50 ratifying countries (there will inevitably be more), South Africa, has ever been a nuclear-weapons state and more than four-fifths of treaty ratifiers so far are already located within nuclear-weapon-free zones.

With the re-emergence of great-power rivalry and the general deterioration of the global security environment, tackling the issues surrounding nuclear weapons is of growing importance. The question is therefore not whether nuclear-weapons holdings need to be addressed, but rather how, at what pace and with what aim. A world free of nuclear weapons will not necessarily lead to increased global stability, and regional-security and strategic-stability concerns cannot be overlooked or divorced from ambitions to achieve nuclear disarmament. Moreover, to its detractors, the TPNW fails to address how the critical issue of disarmament verification would be accomplished, and risks overshadowing arms-control initiatives that may be more achievable and thus beneficial to international security in the near term.

Two weeks after the TPNW is due to come into effect, on 5 February 2021, the US−Russia New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) is scheduled to expire. While US President-elect Joe Biden will likely look to extend the treaty, that may require cooperation from the outgoing Trump administration. As of mid-November, that seems far from guaranteed. Irrespective of the advent of the TPNW, the loss of New START would be a body blow for substantive nuclear arms control.

Banning the bomb

The TPNW makes the possession, development, use or threat of use of nuclear weapons contrary to international law. Its supporters argue that it strengthens the legal structures and political norms against the possession and use of nuclear weapons and therefore buttresses other instruments of nuclear arms control and disarmament.

Conversely, the treaty could be seen as a distraction from bolstering what remains of the nuclear arms-control framework, including the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and as creating uncertainty in respect of other mechanisms, such as the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. There is little sign of consensus between the TPNW’s advocates and critics regarding the value of the treaty as a nuclear-disarmament tool. The impasse raises questions about the treaty’s relevance and whether signatories will be able to influence nuclear-weapons policy among nuclear-weapon states and those that shelter under the nuclear umbrella of extended deterrence.

Testing the TPNW

Following negotiations, the TPNW was adopted by the United Nations on 7 July 2017 by a vote of 122 states in favour, with the notable absence of all the declared nuclear-weapons states plus Israel. A goal of the TPNW is to develop political norms against the possession of nuclear weapons. This objective depends on stigmatising these weapons among the states possessing or protected by them through internal and external political pressure.

This aim also hangs on the ability of signatories to persuade nuclear-weapons states that any holding of these weapons, irrespective of number, does not provide deterrence − and that national and collective security would benefit from the relinquishing of such holdings. All the nuclear-weapons states now view these systems as their ultimate security guarantor, and assuming the moral high ground appears unlikely to succeed alone. For example, while NATO’s 2010 Strategic Concept − the organisation’s most recent statement on its values and objectives − commits the Alliance to the goal of creating conditions for nuclear disarmament, it re-affirms that, as long as there are nuclear weapons in the world, NATO will remain a nuclear alliance. Moreover, considering the various nuclear-modernisation and nuclear-expansion programmes underway among declared nuclear-weapons states, as well as procurements among those protected by the United States’ extended deterrence, a nuclear-weapons policy about-face is highly unlikely.

Finally, the emphasis in any nuclear-related treaty for nuclear-weapons states is likely to remain on the need to ‘trust, but verify’. The scant language on verification in the TPNW is clearly a weakness. Intrusive verification is a crucial element to successful arms control and disarmament initiatives, but the TPNW’s vague obligations and verifications are inadequate.

The TPNW will come into effect at a tumultuous time. Hard state power rather than mutually beneficial collective action appears to be the dominant force in contemporary international affairs. Relations between the US and China and between NATO and Russia remain tense, with worrying scope for miscalculation or misinterpretation. Such an environment makes addressing nuclear-weapons issues and arms control while trying to maintain strategic stability all the more pressing. In its narrowest interpretation, strategic stability is understood as an absence of incentives for states to pre-emptively use nuclear weapons or expand their nuclear arsenals. If states take a broader approach to arms control, bilateral and multilateral engagement can potentially practically address both these issues through developing norms and avenues for discussion on destabilising new technologies and risk-reduction measures. The different approaches to this, in the shapes of the TPNW and New START, will play out against this backdrop.

Stockholm Intl. Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Analysis

The NPT and the TPNW: Compatible or conflicting nuclear weapons treaties?

6 March 2019 Dr Tytti Erästö

The 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was negotiated with the purpose of strengthening the largely unimplemented disarmament pillar of the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Yet, one of the main criticisms against the Treaty has been its alleged incompatibility with the NPT. What is one to make of these conflicting claims? And should the increasing number of TPNW ratifications be seen as good or bad news for the international nuclear order?

References to the NPT in the TPNW

The drafters of the TPNW took great care to avoid any conflict with the NPT. This intention is reflected in their repeated statements highlighting the mutually reinforcing nature of the two treaties, as well as in the TPNW text.

The NPT is explicitly mentioned in the TPNW preamble, which reaffirms that ‘the full and effective implementation of the [NPT], which serves as the cornerstone of the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime, has a vital role to play in promoting international peace and security’. Another, more implicit reference to the NPT is in Article 18, which states that ‘The implementation of this Treaty shall not prejudice obligations undertaken by States Parties with regard to existing international agreements, to which they are party, where those obligations are consistent with the Treaty.’

Some argue that the latter part of the above formulation ‘subordinates the NPT to the ban treaty’. However, this concern is based on the premise that there is an inconsistency between the obligations of the two treaties. But is there such inconsistency?

Legal compatibility of the treaties

Article 1 of the TPNW prohibits the development, deployment, possession, use and the threat of use of nuclear weapons. Its key prohibitions also include the stationing of nuclear weapons on states parties’ territory, as well as the assistance, encouragement or inducement of any activity prohibited by the treaty. These obligations apply equally to all states parties, but they do not bind countries that are outside the treaty. Although none of the nine nuclear-armed states are likely to join the TPNW in the immediate future, the underlying assumption is that they will ultimately be affected by the strong stigmatization of nuclear weapons in the Treaty.

In comparison, in NPT Article II non-nuclear weapon states commit themselves not to acquire nuclear weapons, whereas the five nuclear-armed states parties agree to pursue disarmament in Article VI. More specifically, the latter article requires ‘Each of the Parties to the Treaty… to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.’

Further stressing the long-term goal of nuclear disarmament, the NPT preamble points to the need ‘to facilitate the cessation of the manufacture of nuclear weapons, the liquidation of all their existing stockpiles, and the elimination from national arsenals of nuclear weapons and the means of their delivery pursuant to a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.’

In other words, while the TPNW seeks to make nuclear weapons illegal for all countries, the NPT provided a monopoly on such weapons to the five countries that had proliferated before 1968. This exception and its subsequent acceptance by the nearly universal NPT membership reflected concerns about an uncontrolled spread of nuclear weapons, which were particularly high in the 1960s. At the same time—although it does not mention any specific time limits—the NPT clearly points to the need for the eventual disarmament by the five countries.

While not identical, the core obligations of the two treaties thus seem to be perfectly consistent with one another. For this reason, the recent flurry of legal analyses on the TPNW rarely problematizes the Treaty’s relationship with the NPT, but instead tends to focus on potential inconsistencies with existing security arrangements.

Indeed, the TPNW can be seen as putting the NPT Article VI into practice. (Whether the TPNW actually amounts to the kind ‘effective measure’ envisioned in Article VI or whether it will eventually become the normative framework regulating the complete abolition of nuclear weapons are speculative questions that are best answered with the benefit of hindsight at a later point in time.)

Impact on non-proliferation

While there is no apparent legal incompatibility between the two treaties, critics have argued that the TPNW might jeopardize the NPT’s non-proliferation objectives. One such argument was raised during the TPNW negotiations, when the drafters of the emerging treaty were warned about ‘forum-shopping’—that is, the possibility that non-nuclear weapon states joining the TPNW might choose to opt out from the NPT and thus free themselves from the verification requirements in the NPT.

Although this concern is addressed by TPNW Article 3—which requires states parties to maintain their existing IAEA safeguards ‘without prejudice to any additional relevant instruments’—concerns about forum-shopping continue to be made by critics. As noted by a recent report by the Norwegian Academy of International Law, however, TPNW ratification ‘by no means alters the requirements for withdrawal from the NPT’, nor does it ‘offer states a legal pretext to exit from the NPT’.

While it is possible that some countries do decide to withdraw from the NPT, the TPNW is unlikely to be the sole reason. Rather, the issue should be seen in the context of the broader legitimacy crisis within the NPT, which is caused mainly by the lack of implementation of Article VI, and which also contributed to the negotiation to the TPNW. States might also leave the NPT based on ‘extraordinary events’ (referring to Article X of the NPT) that they perceive as having jeopardized their ‘supreme interests’ and thus calling for the development of a nuclear deterrence capability of their own.

A related criticism is that the TPNW missed the opportunity to incorporate the highest existing standard for nonproliferation verification by not obligating non-nuclear weapon states to accept the Model Additional Protocol to the IAEA Comprehensive Safeguards (INFCIRC/540). Instead, the Treaty sets the IAEA Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (INFCIRC/153 (Corrected)) as the minimum non-proliferation verification requirement. According to critics, this ‘outdated system… has been known for a quarter century to be inadequate to the challenge of rooting out clandestine nuclear activity’.

The specific mention of INFCIRC/153 (Corrected) in the TPNW can nevertheless be seen as an improvement from the NPT Article III, which does not specify any particular safeguards standard. Moreover, as noted above, the TPNW does not allow states parties to downgrade their existing verification arrangements, and hence it does not undermine the existing Model Additional Protocol agreements which are already in force in 134 countries, should they decide to join the Treaty.

Quite a different concern is that—to the extent that it succeeds in delegitimizing nuclear deterrence—the TPNW could undermine umbrella states’ trust in extended deterrence and thus drive them to acquire nuclear weapons of their own. This argument assumes that the USA—currently the sole provider of extended nuclear deterrence and one the staunchest opponents of the TPNW—would be disproportionately influenced by the TPNW’s normative standards, whereas its allies would continue to subscribe to the logic of deterrence. While there are long-standing credibility issues related to nuclear security guarantees, it is somewhat difficult to imagine that the TPNW would be the decisive factor pushing umbrella states to acquire nuclear weapons.

The concern about deterrence nevertheless captures one of the most fundamental points of divergence underlying the debate over the TPNW—that is, whether the perceived benefits of nuclear deterrence on national security and strategic stability justify risking the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons use. While the TPNW is very clear in rejecting this logic, pointing to the ‘effects on human survival, the environment, socioeconomic development, the global economy, food security and the health of current and future generations’, the NPT neither prohibits nor embraces deterrence. (However, critics have long argued that NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements are inconsistent with Article I of the NPT, in which states parties commit themselves ‘not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly.’)

Conclusion

It would be difficult to make the case of legal incompatibility between the TPNW and the NPT, as the former so clearly builds on NPT Article VI on disarmament. Instead, the perceived incompatibility between the two treaties mainly has to do with the indirect negative consequences that the TPNW could potentially have on the NPT’s non-proliferation objectives. While it is indeed possible that some non-nuclear weapon states could withdraw from the NPT and umbrella states might lose faith in extended deterrence, the TPNW is unlikely to be the sole or even primary trigger for such developments.

Essentially, the dispute over the TPNW is based on political disagreement regarding how to advance nuclear disarmament. While the NPT reflected the need to prioritise non-proliferation over the long-term goal of disarmament, the

TPNW represents the view that—half a century after the adoption of the NPT—progress on disarmament is long overdue.

At the same time, the TPNW seeks to promote disarmament by delegitimising the continued possession of nuclear weapons by all countries, including the five nuclear-armed members of the NPT. This puts the Treaty at odds with the existing nuclear order. However, it does not make the TPNW incompatible with the NPT; in addition to codifying the existing nuclear monopoly of a few countries in 1970, the NPT also foresaw the need for change, and therefore cannot be used indefinitely to defend the status quo.

Dr Tytti Erästö is a Senior Researcher in the SIPRI Nuclear Disarmament, Arms Control and Non-proliferation Programme.

ICAN / Acronym Institute Analysis

Why the UK needs to join the TPNW Treaty

The TPNW provides a unique opportunity for progress, after decades of deadlock in multilateral forums. It gives nuclear-armed states such as the UK the chance to redouble their efforts and commitments to achieving the elimination of all nuclear weapons.

The TPNW is multilateral disarmament. It developed out of a multi-year international process over the past decade. It was led by a number of states parties to the NPT, who worked with civil society to examine evidence about the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, and the risks to people around the world by their continuing possession by a handful of states.

Based on the evidence, the majority of the world’s countries concluded that the prohibition of nuclear weapons was the only sensible course of action, and that this was a necessary step to bring about their elimination. In 2016, the UN General Assembly mandated negotiations on a treaty, and in 2017 the TPNW was negotiated in a UN forum open to all UN member states.

The risks of an accidental or deliberate detonation of a nuclear weapon have not gone away since the Cold War – even increasing in recent years. Nuclear weapons in anyone’s hands threaten our national and international security. The theory of nuclear deterrence is based on possessing and threatening to use nuclear weapons. Even if governments believe in deterrence, the possession and deployment of nuclear weapons can result in misjudgments and crisis escalation. That’s the kind of situation that can lead to nuclear weapons being detonated, by accident or intention.

In the UK, nuclear weapon convoys on our roads bring the hazard of nuclear accidents very close to home. These risks make the task of eliminating nuclear weapons ever more urgent. The UK government is committed to the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons – along with most other nations – and frequently expresses this commitment to Parliament and at the UN. For a world free of nuclear weapons to be achieved, the UK will have to commit to the prohibition of these weapons at some point. This is the only global nuclear weapons prohibition treaty that exists, so the UK needs to come on board or face perpetual proliferation.

The UK already has a legal obligation to negotiate on disarmament, from its membership of the NPT. This means that joining the TPNW would be a fulfilment of international obligations that the UK has already legally undertaken. In banning the use and possesion of nuclear weapons, the TPNW is similar to other treaties dealing with weapons of mass destruction – the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention. The UK has joined both these treaties.

We once considered chemical and biological weapons strategically important, but now find them abhorrant because of their terrible effects. The Scottish government and parliament are already in favour of the TPNW, but they are being disregarded by the Westminster government, which is dependent on Scottish bases to stockpile and deploy Trident nuclear weapons. This was, and remains, a key issue in the debate on Scottish independence.

The current positions of the devolved government and parliamentary representatives of Scotland also weaken the UK government’s claim of a full democratic mandate to maintain and renew the UK’s nuclear weapons. The UK government should therefore stop speaking against the TPNW, and commit to:

- Joining the treaty as soon as possible;

- Participating in its meetings as an observer in the interim;

- Encouraging other states to join; and

- Consulting with the devolved government in Scotland on this issue.

The UK should use the TPNW as the framework through which it eliminates its nuclear weapon stockpiles. The UK should not tie its joining the treaty to the actions of other states. This would be a recipe for inaction and further deadlock. The TPNW offers an opportunity for the UK to join the majority of the world’s countries that have agreed that weapons with such destructive and horrific effects have no place in achieving any form of genuine security.

The treaty’s obligation to provide assistance to the victims of nuclear weapon use and testing will strengthen good practice among states in meeting the medical, social and economic needs and realising the rights of people affected by other inhumane and prohibited weapons, including British nuclear test veterans and their families. UK engagement with the TPNW would provide an opportunity for global leadership on abolishing all WMD. The elimination of Trident, combined with the Ministry of Defence’s research on disarmament verification, would put the UK in a unique position to contribute to international security and increase jobs in these areas where Britain has the skills and expertise to lead the way.

UNA-UK’s Analysis

https://www.una.org.uk/news/historic-moment-disarmament-nuclear-ban-enter-force-january-2021

HISTORIC MOMENT FOR DISARMAMENT

Nuclear ban to enter into force in January 2021

23 October 2020

On 24 October 2020 – the UN’s 75th birthday – the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) gained its 50th ratification meaning that this ground-breaking Treaty which comprehensively prohibits nuclear weapons and related activities will become legally-binding international law 90 days later on 22 January 2021.

Following tireless campaigning by civil society, mayors, faith leaders and nuclear weapons survivors under the banner of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the TPNW was created in 2017 with the support of 122 countries – two thirds of the UN’s membership. Given the international prohibitions on biological and chemical weapons created in the second half of the 20th century, the international community has now successfully addressed the lack of a corresponding treaty to ban the other major class of weapons of mass destruction: nuclear weapons.

The Treaty is a legally binding prohibition that will not only create an ever-growing patchwork of sovereign nuclear weapons-free zones, but also require States Parties not to assist the weapons programmes of nuclear armed States or support the concept of nuclear deterrence. The Treaty addresses the catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons and takes the approach that nuclear weapons are a concern of for all people in all countries, not just those in possession of these weapons. Alongside the prohibitions, the Treaty provides recourse to assistance for individuals affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons, as well as measures for environmental remediation.

The entry into force of the TPNW will bring significant pressure to bear on the UK Government, which does not currently support the Treaty.

Analysis on the UK’s relationship with the TPNW

While the UK is committed to nuclear disarmament under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – a Treaty it views as the “cornerstone” of nuclear security – it’s approach to the TPNW, which clearly complements the fundamental objectives of the NPT, has been combative.

Rather than engaging with the process, the UK has variously boycotted, protested and dismissed the TPNW, the negotiations which led to it, and those supporting it. The UK’s failure to participate in the string of multilateral discussions on nuclear disarmament, including those mandated by the UN, is irreconcilable with its international obligations under Article 6 of the NPT which requires the UK to participate in negotiations on disarmament in “good faith”. Such boycotts were also at odds with the outcome document of the 2010 NPT Review Conference (which the UK itself signed up to).

Most concerningly, the UK’s repeated labelling of the TPNW as a “divisive initiative” will itself serve to deepen divisions and make it harder to reach consensus agreements on nuclear security in other multilateral forums, such as the NPT. By erroneously casting the TPNW as a threat to the NPT rather than embracing the ways it can contribute to disarmament, the UK is guilty of what it accuses TPNW supporters of doing: undermining the NPT.

Such actions demonstrate little awareness of the reason for the TPNW’s emergence – namely the widely perceived failure of nuclear weapons states to make sufficient progress on their disarmament commitments. The UK’s inflammatory actions also puts it unequivocally at odds with UN guidance on the issue. A statement made by UN High Representative on Disarmament Affairs, speaking in Parliament at an event organised by UNA-UK, implored nuclear weapons states to desist from undermining the TPNW, saying: “don’t ignore it, don’t attack it.

Irrespective of the UK Government’s position, the TPNW’s impact will be felt. Cities, local authorities and mayors are getting behind the Treaty and renouncing their political support for the UK’s nuclear weapons industry and the stockpiling and movement of hazardous materials it necessitates. The Scottish Government publicly endorses the Treaty. Major banks, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds across Europe are divesting from nuclear weapons and related industries. Internationally, UK’s divisive approach to a process supported by a majority of UN Member States damages the UK’s standing and puts strain on the UK’s relations with a large swathe of the international community.

In an article published by the Byline Times, UNA-UK’s Head of Campaigns Ben Donaldson commented:

“The ground is moving under the UK’s feet. Whether or not the UK supports the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, the impact will be felt. The Treaty is popular with States the UK is looking to strike trade deals with and the UK is finding itself increasingly diplomatically isolated on this issue. As well as being immoral, the UK’s current position of variously ignoring and attacking the Treaty and its supporters is unsustainable. A large majority of countries have made it clear they have lived in fear of nuclear fallout for too long and want action.”

The UK and its nuclear allies are clearly feeling the pressure. Earlier this week the US sent a letter to States that have ratified the TPNW urging them to withdraw their support.

UNA-UK has consistently argued that the UK should start engaging constructively with the TPNW, a position echoed by a 2019 cross-party report by the Lords Committee on International Relations. In the short term this means recognising the strengthening effect the TPNW can have on the NPT, committing to attend Meetings of States Parties as an observer and voluntarily begin implementing the Treaty’s measures to assist affected individuals and remediating the environment. More broadly the UK should explain at the earliest opportunity how it intends to make progress on its international obligation to disarm and announce its future intention to join the TPNW.

Seventy-five years after London hosted the first UN meetings where General Assembly Resolution 1(1) called for a world free of nuclear weapons, there is now a powerful new tool to help make this a reality.

UNA-UK is a proud UK partner of the Nobel Prize-winning ICAN coalition and has campaigned on nuclear disarmament since its founding in 1945.

UNA-UK’s evidence to the Foreign Affairs Committee

UNA-UK’s evidence to the Lords IR committee

Read more about UNA-UK’s recommendations

Read Together First’s Stepping Stones report recommending progress on disarmament